Continent Urinary Diversion

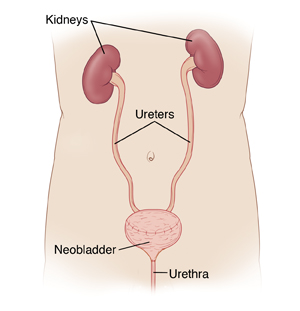

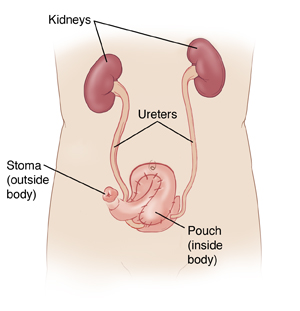

Continent urinary diversion is surgery to make a new way for urine to pass out of the body. The surgery may be needed if your bladder is diseased or damaged. During the surgery, a new bladder (neobladder) may be created. Or an internal pouch may be created. This is done using a piece of your own intestine (bowel).

Two types of urinary diversion

To collect urine inside your body, you may have a neobladder or an internal pouch. Your healthcare provider will discuss which choice is best for you. A different option includes creating a tube that continually drains urine into an external bag. This is called a urostomy.

-

Neobladder. A neobladder allows urine to follow the normal path out of the body. With a neobladder, you’ll no longer have nerves that signal when your bladder is full. You will need to empty the bladder on a set schedule. To do this, you use your pelvic and belly (abdominal) muscles to help push the urine out of your body. In some cases, you pass a thin tube (catheter) through the urethra into the new bladder to drain urine.

-

Internal pouch. A pouch connects on one end to the tubes (called ureters) that bring urine from the kidneys to the bladder. The other end of the pouch connects to a small, permanent opening (stoma) made in the wall of the abdomen. A valve is created surgically to prevent urine leakage. Most of the time, the stoma is covered with a small bandage. To empty urine from the pouch, you pass a catheter through the stoma into the pouch. This is done on a set schedule. Unlike with some treatments, no bag is needed to collect urine.

Getting ready for surgery

Prepare for the surgery as you have been told. In addition:

-

Tell your healthcare provider about all medicines you take. This includes prescription medicines and over-the-counter medicines, vitamins, herbs, and other supplements. It also includes any blood thinners, such as warfarin, clopidogrel, or daily aspirin. You may need to stop taking some or all of them before surgery.

-

Follow any directions you are given for not eating or drinking before surgery. This includes coffee, water, gum, and mints. (If you have been instructed to take medicines, take them with a small sip of water.)

-

If you have been told to, prepare your bowel for surgery (called bowel prep). This process begins 1 to 2 days before the surgery. Your healthcare provider may tell you to limit your diet to clear liquids. You may also be asked to take laxatives or to give yourself an enema. Follow all instructions you are given.

The day of surgery

The surgery takes 4 to 5 hours. After, you will stay in the hospital for 5 to 7 nights.

Before the surgery begins

-

An IV (intravenous) line is put into a vein in your arm or hand. This delivers fluids and medicines, such as antibiotics. In some cases, a central or arterial line is inserted into a vein somewhere else on the body. Your healthcare provider can tell you more.

-

You may be given a medicine to prevent blood clots in your veins.

-

To keep you pain-free during the surgery, you’re given general anesthesia. This medicine puts you into a state like deep sleep through the surgery. A tube may be inserted into your throat to help you breathe.

-

You may have an epidural to help control postsurgery pain. A small tube is inserted into your back to deliver pain medicine that numbs the lower body. Talk with your healthcare provider, anesthesiologist, or nurse anesthetist about this option.

During the surgery

-

A catheter may be placed into your bladder through your urethra.

-

A cut (incision) is made in the belly.

-

The bladder may be left in place or it may be removed.

-

For a neobladder, a piece of the small intestine is removed. It is attached to the ureters on one end and to the urethra on the other end.

-

For a pouch, the end of the small intestine and first part of the large intestine is removed. A stoma is made in the wall of your lower belly. The piece of intestine is then connected to the ureters on one end and to the stoma on the other.

-

When the surgery is complete, the incision in the belly is closed with stitches or staples.

-

A small tube (drain) may be placed in the belly to help remove excess blood and fluid.

-

Thin tubes (stents) may be placed through the belly into the ureters to the kidneys. These help drain urine during healing.

-

You may need a tube in your nose that extends into your stomach to prevent your stomach from getting swollen. The tube is removed as you get better.

-

If you have a neobladder, a catheter may be placed into it to help drain urine. If you have a pouch, a catheter may be placed through the stoma into the pouch to keep the pathway open. Another catheter may be placed through the belly into the pouch to help drain mucus and urine.

Recovering in the hospital

After the surgery, you will be taken to a recovery room. Here, you’ll wake up from the anesthesia. You may feel sleepy and nauseated. If a breathing tube was used, your throat may be sore at first. When you are ready, you will be taken to your hospital room. While in the hospital:

-

You will be given medicine to manage pain. Let your healthcare providers know if your pain is not controlled.

-

You’ll first receive IV fluids. In a day or so, you will start on a liquid diet. You will then slowly return to a normal diet.

-

As soon as you’re able, you will get up and walk.

-

You’ll be taught coughing and breathing methods to help keep your lungs clear and prevent pneumonia.

-

A healthcare provider will show you how to care for your new bladder or pouch and stoma. You’ll also learn how to care for any drains and tubes that you have. You may be taught to flush your pouch with fluid, to remove mucus.

Recovering at home

After your hospital stay, you will be released to an adult family member or friend. Have someone stay with you for the next few days to help care for you. Recovery time varies for each person. Your healthcare provider will tell you when you can return to your normal routine. Until then, follow the instructions you have been given. Make sure to:

-

Take all medicine as directed.

-

Care for your incision as instructed. If you go home with a drain or catheter, take care of them as you were shown.

-

If you have a stoma, care for it as instructed.

-

Follow your healthcare provider’s guidelines for showering. Don't swim, take a bath, use a hot tub, or do other activities that may cover the incision with water until your healthcare provider says it’s OK.

-

Not do any heavy lifting or strenuous activities as directed.

-

Not drive until your healthcare provider says it’s OK. Don’t drive if you’re taking medicines that make you drowsy.

-

Walk a few times daily. As you feel able, slowly increase your pace and distance.

-

Not strain to pass stool. If needed, take stool softeners as advised by your healthcare provider.

-

Do pelvic (Kegel) exercises as directed.

Call 911

Call 911 if you have chest pain or trouble breathing.

When to call your healthcare provider

Call your healthcare provider right away if you have any of the following:

-

Fever of 100.4° F ( 38°C ) or higher, or as directed by your healthcare provider

-

Symptoms of infection at an incision site, such as increased redness or swelling, warmth, pain that gets worse, or bad-smelling drainage

-

Pain, redness, swelling, odor, or drainage at the stoma site

-

Little or no urine output for longer than 4 hours

-

Burning or pain when passing urine, or frequent need to pass urine

-

Bloody urine with clots

-

Problems with any drains, stents, or catheters

-

Nausea or vomiting that doesn’t go away

-

Pain that can't be controlled with medicine

Follow-up care

You will have follow-up visits so your healthcare provider can check how well you’re healing. Stitches, staples, or tubes will be removed. You may be taught how to drain your pouch using a catheter. If you have a neobladder, you may be taught pelvic floor exercises to strengthen the muscles around it. This helps prevent urine leakage. You and your healthcare provider can also discuss any further treatment you may need.

Risks and possible complications

Possible risks of this procedure include:

-

Bleeding (you may need a blood transfusion)

-

Infection

-

Blood clots

-

Pneumonia or other lung problems

-

Incontinence

-

Abnormal levels of vitamins or minerals in the blood, needing lifelong medicine

-

Backup of urine in the ureters and kidneys

-

Problems with the neobladder or pouch

-

Development of stones in the neobladder or pouch

-

Problems with the stoma

-

Scarring and narrowing of the ureters

-

Risks of anesthesia. The anesthesiologist or nurse anesthetist will discuss these with you.

Online Medical Reviewer:

Marc Greenstein MD

Online Medical Reviewer:

Raymond Kent Turley BSN MSN RN

Online Medical Reviewer:

Tennille Dozier RN BSN RDMS

Date Last Reviewed:

3/1/2022

© 2000-2025 The StayWell Company, LLC. All rights reserved. This information is not intended as a substitute for professional medical care. Always follow your healthcare professional's instructions.