When Your Child Has a Hypoplastic Right Ventricle: Tricuspid Atresia

Your child has a heart problem called hypoplastic right ventricle. This means that the right ventricle is either too small or missing. The most common heart problem that includes a hypoplastic right ventricle is called tricuspid atresia.

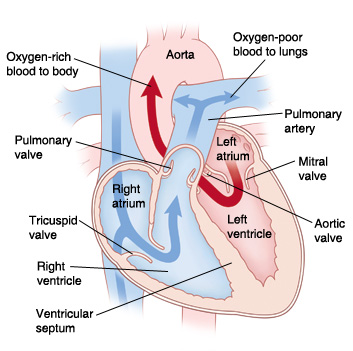

The normal heart

-

The heart is divided into 4 chambers. The 2 upper chambers are called atria. The 2 lower chambers are called ventricles. The heart has 4 valves. The valves open and close. They keep blood flowing forward through the heart.

-

In a normal heart, oxygen-poor blood returns from the body and fills the right atrium. This blood flows across the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle. The right ventricle pumps this blood across the pulmonary valve through the pulmonary artery to the lungs. There, the blood receives oxygen. Oxygen-rich blood returns from the lungs and fills the left atrium. This blood then flows across the mitral valve into the left ventricle. The left ventricle pumps this blood across the aortic valve to the aorta. From there, it travels out to the body.

-

The ductus arteriosus is a normal part of a baby’s heart before birth. It’s a blood vessel that connects the pulmonary artery and the aorta. It lets blood flow between the 2 vessels. It normally closes shortly after birth. If it remains open, it’s called a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA).

-

The foramen ovale is also a normal part of a baby’s heart before birth. It’s an opening in the wall (atrial septum) between the atria. It normally closes a few weeks after birth. If it remains open, it’s called a patent foramen ovale (PFO).

|

| In a normal heart, oxygen-poor blood is pumped to the lungs from the right ventricle. Oxygen-rich blood is pumped to the body from the left ventricle. |

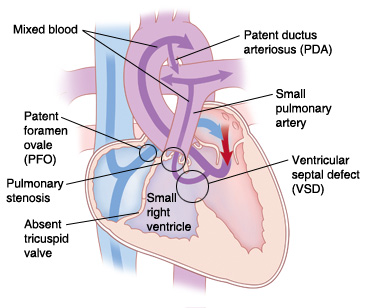

What is tricuspid atresia?

-

With tricuspid atresia, the tricuspid valve is missing or completely blocked off. Normally, this valve allows oxygen-poor blood to flow from the right atrium to the right ventricle. With no valve, blood can't reach the right ventricle. As a result, the right ventricle is small. And there is usually narrowing (stenosis) of the pulmonary valve and pulmonary artery.

-

These problems with the right heart structures keep blood from being pumped to the lungs in the normal way.

-

Normally after birth, the PFO and PDA close. With tricuspid atresia, they remain open, allowing blood to flow through the heart and reach the lungs.

-

A PFO allows oxygen-poor blood from the right atrium to flow through the atrial septum. This is the dividing wall between the 2 upper chambers of the heart. It mixes with oxygen-rich blood in the left atrium. This causes mixed blood (blood with some oxygen) to flow into the left ventricle. It's then pumped through the aorta to the body. This blood contains less oxygen than normal. So, your child’s skin, lips, and nails may look blue. This is called cyanosis.

-

A PDA allows some of the blood moving through the aorta to flow into the pulmonary artery. As a result, some blood can reach the lungs and get oxygen. If the ductus arteriosus closes after birth, not enough blood flows to the lungs. This makes cyanosis worse and may be life-threatening.

-

Most children with tricuspid atresia have another heart defect called a ventricular septal defect (VSD). This is a hole in the wall (ventricular septum) between the ventricles. The hole lets some blood flow from the left ventricle into the small right ventricle. Some of this blood can flow across the pulmonary valve into the pulmonary artery and reach the lungs.

-

Some children with tricuspid atresia may also have another problem called transposition of the great vessels (TGA). This is when the great vessels (pulmonary artery and aorta) arise from the incorrect ventricles.

|

| With tricuspid atresia, blood can’t be pumped to the lungs in the normal way because of problems with right-sided heart structures. |

What causes tricuspid atresia?

Tricuspid atresia is a congenital heart defect. This means your child was born with it. The exact cause is unknown. Most cases seem to occur by chance.

What are the symptoms of tricuspid atresia?

A child most often has severe symptoms shortly after birth. These can include:

-

Skin, lips, and nails look blue (cyanosis)

-

Trouble breathing or rapid breathing

-

Poor feeding

-

Poor weight gain and growth

-

Tiredness

-

Child becomes gray and cold, and the heart may stop beating (circulatory collapse)

How is tricuspid atresia diagnosed?

-

Tricuspid atresia may be seen on fetal ultrasound before a child is born. This test uses sound waves to form a picture of the baby’s heart. This test can be done as early as when the mother is 12 weeks pregnant.

-

If it isn’t found before birth, signs of a heart problem may be noted during a physical exam shortly after birth.

-

If a heart problem is suspected, your child will be referred to a pediatric cardiologist. This is a who diagnoses and treats heart problems in children. To confirm tricuspid atresia, several tests may be done. These include:

-

Chest X-ray. X-rays are used to take a picture of the heart and lungs.

-

Electrocardiography (ECG). The electrical activity of the heart is recorded.

-

Echocardiography (echo). Sound waves are used to create a picture of the heart and look for structural problems and other problems.

How is tricuspid atresia treated?

Tricuspid atresia can be treated with heart surgery. A series of surgeries is needed. They are done in 2 or 3 stages. Whether the first stage needs to be done depends on the amount of blood flow to the lungs. Your child’s healthcare provider will discuss choices with you.

Newborns may be given IV medicine to keep the ductus arteriosus open. This lets blood keep traveling to the lungs to get oxygen.

Your child may need a procedure called a balloon septostomy. This may be done to help until a complete repair can be done. During this procedure, a thin, flexible tube (catheter) with a balloon on the end is used. It's guided through a blood vessel into the heart. The balloon is inflated to widen the PFO. This allows blood to mix freely between the atria. More oxygenated blood can then reach the body.

What are the long-term concerns?

Tricuspid atresia is a challenging heart problem to treat. After surgery, your child may have ongoing heart problems. They may need medicines to manage symptoms and improve heart function. Your child may also need more surgery. Your child needs follow-up visits with the cardiologist for the rest of their life.

In many cases, children with tricuspid atresia can be active. How active will vary with each child. Ask the cardiologist what activities your child can do safely.

Your child may need to take antibiotics before having any surgery or dental work. This is to prevent infection of the heart or valves. This is called infective endocarditis. The cardiologist will give you directions for this.

Online Medical Reviewer:

James Beckerman MD

Online Medical Reviewer:

Scott Aydin MD

Online Medical Reviewer:

Stacey Wojcik MBA BSN RN

Date Last Reviewed:

9/1/2022

© 2000-2025 The StayWell Company, LLC. All rights reserved. This information is not intended as a substitute for professional medical care. Always follow your healthcare professional's instructions.